Channeling "the Great Dissenter"

May 27, 2020

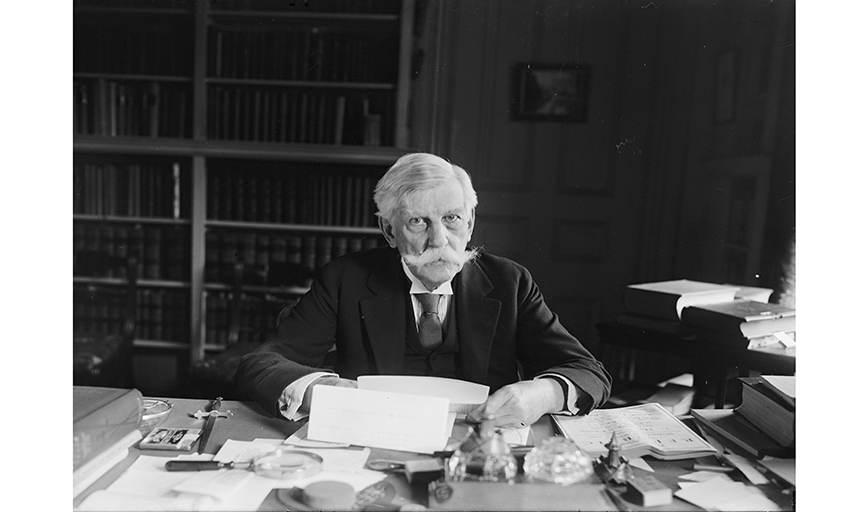

Below is a portion of a story about how the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. brought a Roanoke College professor through a difficult period. The result is a one-act, one-man play about Justice Holmes, titled, simply, “Holmes.” The play will be the first to be performed on the floor of the U.S. Supreme Court. To read the full version of this story, visit the web version of Roanoke College magazine and turn to page 10.

The project began in darkness.

Six years ago, Dr. Todd Peppers’ mother was diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease), and Peppers was having trouble sleeping. He searched for ways to keep his mind occupied in the wee hours and found solace in a vast collection of literature on the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Peppers — Henry H. & Trudye H. Fowler Professor in Public Affairs at Roanoke College — has long been fascinated with Holmes, who served on the Supreme Court from 1902-1932 and has become one of the most widely cited and researched judges in the court’s history.

Over the years, Peppers has collected articles, books and collections of Holmes’ letters. Several of his students have helped him gather these documents, he said. Years ago, he and a student research assistant went up to Harvard Law School and sorted through Holmes’ personal papers. The research from that trip helped inform multiple articles, even a play based on Holmes' life, Peppers said.

Peppers’ work on the play underscores the importance of being well-rounded and learning a variety of skills, he said.

“I told my dad, who was an academic, that in some ways this play is an advertisement for a liberal arts education,” Peppers said. “When I was an undergraduate at Washington and Lee, I took classes in history, literature, and creative writing. I was a philosophy major who did theater. And then I went to law school. All of these experiences contributed to writing a play.”

Though he started reading through these documents as a late-night task to ease his mind, Peppers began recognizing patterns in Holmes’ writing. Peppers took out a pen and started picking out frequent topics and phrases.

“At some point, I don’t know when, suddenly an idea of writing about what I was marking up came to me,” Peppers said. “And I thought, ‘Maybe a play.’”

But he’d never written a play. Peppers has written books and articles, but never a play. He envisioned a one-person play, and he started buying and studying one-person plays about historical figures: “The Belle of Amherst” about Emily Dickinson, “Give ‘Em Hell, Harry” about Harry Truman, and others.

Peppers had an enormous amount of material to sort through when it came to Holmes. Holmes’ distinctive sense of humor and way of speaking have made him a popular figure for historians and legal experts to dissect. Clare Cushman, resident historian for the Supreme Court Historical Society, said Holmes stands out in the court’s history.

“Holmes is one of the wittiest and best writers ever to have sat on the court,” Cushman said. “That man never turned a phrase that was mundane or cliché.”

I told my dad, who was an academic, that in some ways this play is an advertisement for a liberal arts education.

Dr. Todd Peppers, Henry H. & Trudye H. Fowler Professor in Public Affairs

As Peppers noticed more and more of these Holmes-isms, he began collecting them. He compiled a Holmes glossary, including phrases such as “taking a whack at life,” which pops up a few times in the play.

But to form a story and make deeper observations about Holmes’ life, Peppers had to fill in some gaps. He had to read between the lines a bit. Having published academic books, essays and studies, Peppers was used to fact-checking every claim and every reference. This was a new experience.

“When you’re a social scientist or a legal scholar, you’re very careful,” Peppers said. “Every source is documented and checked and double-checked. This play is historical fiction. Eighty, 85 percent of it is completely accurate. Much of the words are Holmes’ himself, from the letters, but 15 to 20 percent of it is what I call ‘informed speculation.’ Some of the most intimate things, you’re guessing at.”

Those private matters included, principally, the impact that Holmes’ experience in the Civil War had on his life. That would eventually form the backbone of the play, but Peppers wanted to consult a few others.

When Peppers approached Cushman with a draft of his one-man Holmes play, Cushman could barely contain her elation. The two of them had worked together on essays and articles in the past, Cushman said, and she’d come to respect Peppers’ expertise, particularly when it came to Supreme Court clerks.

Cushman has read a few plays regarding Supreme Court justices, including plays about Thurgood Marshall and lesser-known former Chief Justice Edward Douglass White. She read through Peppers’ draft and saw in it, great potential.

This being Peppers’ first attempt at playwriting, he and Cushman thought the script could use some polishing. Cushman referred Peppers to Mary Hall Surface, an accomplished playwright, director and dramaturge in Washington, D.C. Peppers liked the idea, but wondered about the actual function of a dramaturge. Essentially, he learned, it was a consultant and editor for a play.

Cushman initially figured Surface was too busy to work as the dramaturge for this play, but thought she could refer Peppers to someone else who could give Peppers pointers about how to turn his potential-laden script into something more entertaining and accessible for audiences.

Then Surface read the play.

“When I got it and I read it, I thought, ‘This is fascinating material,’” Surface said. “So I decided, why not start a conversation with Todd myself?”

Surface started talking with Peppers in 2018. They set to work turning the script into a piece of theater with a more dramatic structure.

“When it came to me, it was filled with wonderful material, extraordinary research,” Surface said. “Holmes’ language is so rich and evocative and filled with images, and he spins a good yarn and has some great one-liners so there was fantastic material.”

Particularly, Surface wanted to see more conflict in the play. She talked to Peppers about an approach called “the spider under the table.” As Peppers explained, everyone has “spiders,” little bits of conflict in their life that usually remain out of view. Then, an event brings that “spider” out into the open, and the character has to confront that conflict.

In the case of “Holmes,” the titular character keeps his Civil War experiences and the loss of his wife hidden away. Then, on his 90th birthday, Holmes is asked to give a radio address to the nation (which actually did happen, on March 8, 1931). As he considers what to say to the country, Holmes wades through his guilt, grief and trauma. The speech brought out the “spider” of the war into view; the audience will see how Holmes grapples with it.

Peppers said that Dr. Richard Smith, vice president and dean of Roanoke College, was extremely helpful and supportive of the project. Smith approved of Peppers using funds from Peppers’ endowed chair status at the College to hire Surface. Endowed chair funds are offered to professors outside their salary to assist with research and other academic endeavors.

“It's because of the endowed chair that I was able to write the play, avail myself of help from some talented professionals, and push it over the top," Peppers said.