Student researchers contribute to the Genealogy of Slavery

September 30, 2022

Officially, the Genealogy of Slavery project at Roanoke College’s Center for Studying Structures of Race this summer involved research to develop a database of information about enslaved people in Southwest Virginia before and during the Civil War.

Unofficially, the student researchers were working to restore the names and stories of people who have been virtually erased from history.

Six students conducted research on the project this summer, each tackling a different aspect. Their aim was to gather names and information about enslaved individuals who worked to build and maintain Roanoke College in its earliest days, and to investigate the centrality of enslaved people to the development of Roanoke County. So far, the project has identified the names of approximately 2,500 individuals who were enslaved in Roanoke County.

The student research team included Casey McGirt, a junior psychology major from Boones Mill; Michele Eaves, a junior sociology major from Roanoke; Sydney Pennix, a junior psychology major from Roanoke; Isabella “Reece” Owen, a history major from Salem; Ivey Kline, a senior history major from Rockville; and Ashtyn Porter, a senior creative writing and international relations double major from Midlothian. Jesse Bucher, college historian and director of the Center for Studying Structures of Race (CSSR), and Whitney Leeson, professor of history and anthropology, both worked with the research team. The research is funded by The CIC’s NetVUE Grant for Reframing the Institutional Saga.

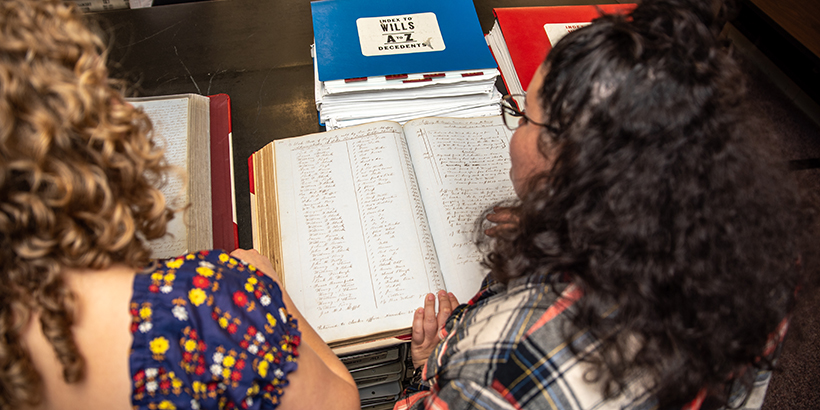

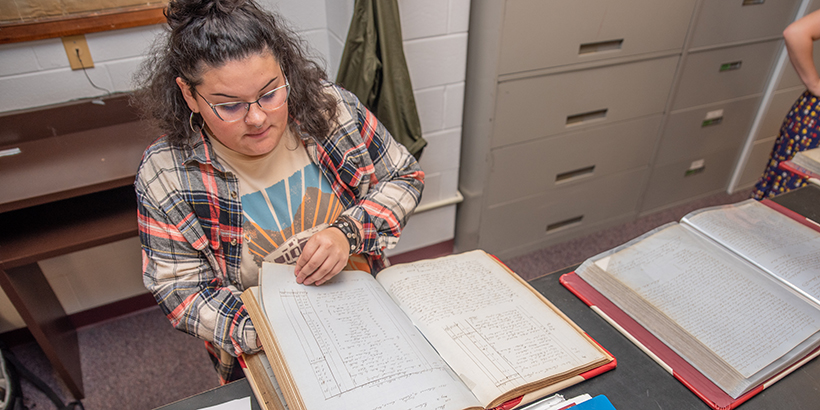

Researchers spent most of their time in the Roanoke County archives, located in the Records Room at the nearby Roanoke County Courthouse. Each student focused on a specific type of source, such as will books, birth register, death register, and inventory and appraisal books (estate property records).

The research itself involved poring over large, bound books with old, handwritten records in search of references to enslaved people. Because computers are not allowed in the Records Room, students had to make notes by hand. The record books detail the final wills and testaments of Roanoke County residents, every birth or death in the county, and inventory lists and financial details of the estates of county residents. Researchers noted dates, years and details recorded in the various books. They also made notes about individuals or property they wanted to follow up on in another record book.

Eaves, for example, read through a book that listed a resident’s assets. “Unfortunately, many of their assets were human beings,” she said. “For example, one woman left her entire enslaved population to her nephew, then he later willed them to someone else. I have been tracking the migration of those enslaved people within the area. Other times, someone may have intended for them to be inherited, but that doesn’t mean it happened if emancipation occurred before the person died.”

Sometimes their research overlaps, as in the case of Sarah Betts, a wealthy property owner in Roanoke County who owned around 50 enslaved people. At almost the same moment, two students mentioned her name as they came across details in different record books.

Owen remembers writing "Sarah Betts January 1837” in her notes at almost the same moment McGirt, who was working in a death registry, said “Sarah Betts died in January 1857.”

“Wow, that was a very goosebumpy moment,” Owen said. After consulting Bucher, they found that Kline had already conducted extensive research on Betts. “It was a very cool moment because it’s so connective. And then we found out the plantation and house she owned were still standing. It’s a closed property, but we did get close to it and were able to look from a distance. It’s so very haunting.”

The students found that Betts granted manumission, or legal release from slavery, to three of the people she enslaved,they still had to work for up to 12 years to earn their “value” in order to be free.

In addition to working in the Records Room, the team conducted field research with CSSR curator Lacey Leonard. That included traveling to the University of Virginia to see its memorial to enslaved people formerly owned by the university; visiting Poplar Forest, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Bedford, Virginia; and visiting the local site of Sarah Betts’ home.

For the research team, absorbing and documenting facts about people who were enslaved was emotionally difficult work. Enslaved individuals were viewed as property, often not even named in the records, but assessed for their “value” in the same way as other kinds of property.

“I went through the first and fifth inventory books, and you’ll see when someone passes away, another person is appraising their property,” Pennix said. “You'll see farm equipment listed, household items, and then a section for horses and cows. Black people are listed there, like there’s no divide. So often they were considered just basic property, not as human beings or families or children. And they have prices. And if they are older or disabled, you can see the price is knocked down. It’s hard to read.”

History is all about the past but from every conversation we’ve had as a group, it’s very much alive. There is an ongoing connective tissue between what we are studying and now.

Michele Eaves, a junior sociology major

The team often read about enslaved families who were split up by an owner’s will or passed down to younger generations of the owner’s family.

“Sometimes, the owner doesn’t want to split up an enslaved family, but then they give a favorite slave to their daughter, knowing when the daughter grows up and gets married, she will take that enslaved person with her,” said Porter. “They’ve made a lot of concessions in this logic of enslavement. That’s consistently cruel and dehumanizing.”

Students were also disturbed by the inaccessibility of Black history, which makes it more difficult for Black families to do genealogy. Most slavery records, including local archives, are not online, and physical sites are typically open limited hours on weekdays.

“These records are not accessible to the average working person,” Kline said. “One of the big points of the project is to make this history known but also to make it easily findable. We’ve worked full-time for two summers to do this research.” The students hope the database will make it easier for those trying to research their family history. Most of the students were not history majors, but the conversations that developed didn’t surprise Bucher. “Many of them are interested in things that have a social impact, such as counseling or social work or working in a library setting. They all talk about careers that rely on being compassionate and communicating well with other people.”

“History is often thought of as much like Latin, like a dead language. History is all about the past,” Eaves said. “But from every conversation we’ve had as a group, it’s very much alive. There is an ongoing connective tissue between what we are studying and now... Putting in the time and reading these documents, it’s been a great opportunity.”

Because of the nature of the research, the students are engrossed in the details of life around the time of the Civil War, and they see how the culture evolved over time – or sometimes didn’t evolve. The students are passionate about connecting the dots between history and the cultural challenges of the modern era.

“Black history is American history and vice versa,” Pennix said. They’re not two separate things, they are built on top of one another. It’s important that we merge the two.”

Four of the students will continue to work with CSSR during the academic year, following up on the research conducted and entering the information they gathered into a database.

The researchers will be presenting their work in several academic venues. Kline will present a research paper at the Council of Independent Colleges Symposium on Remembering and Reckoning with Slavery’s Legacies at Sewanee. Bucher will present the research at a Universities Studying Slavery conference at U.Va. And the six student researchers will be involved in a CSSR open house on October 13, when they will serve as hosts for a walking tour of campus.

Student researchers with the Center for Studying Structures of Race

Student researchers work to develop a database as part of the Genealogy of Slavery research project.

Student researchers with their research supervisor. From left to right: Ivey Kline, Casey McGirt, Sydney Pennix, Dr. Jesse Bucher and Reece Owen.

Ivey Kline and Casey McGirt look through will records in the Roanoke County Records Room.

An example of the handwritten record books used for the research.

Casey McGirt researches in a death registry.

Sydney Pennix and Reece Owen look through records at the Roanoke County Records Room.

Reece Owen and Sydney Pennix discuss what they are finding with Jesse Bucher.